Felix is a photographer and filmmaker (DoP Director of Photography) since 2012. Currently he is based out of Berlin, Germany. He has worked for and with Governments in Europe (Germany), Africa (Burkina Faso, Comoros, Kenya, São Tomé e Principe, South Africa, Mozambique), Asia (China, Vietnam) and the Caribbean (Belize).

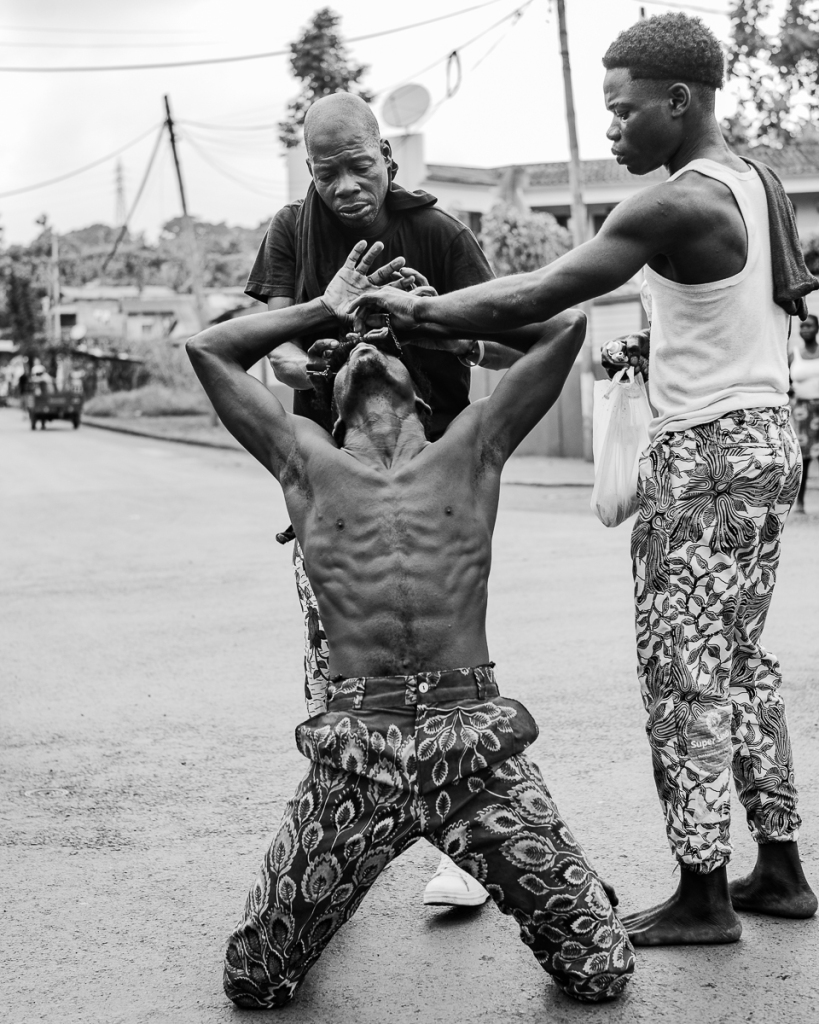

Djambi

Felix Vollmann, a Berlin-based documentary photographer, has created a compelling visual narrative titled São Tomé 2023/2024, focusing on the Djambi ritual in São Tomé and Príncipe. This work is set to be featured in Interpubliq Magazine, highlighting Vollmann’s exploration of the intricate blend of African spiritual traditions and Christianity within the island’s creole culture.

Djambi, a ritual aimed at healing the sick and appeasing ancestral spirits, is characterized by offerings such as food, alcoholic beverages, tobacco, sweets, and music. These elements contribute to a festive atmosphere that serves a sacred purpose. Vollmann’s photography captures the essence of this ritual, emphasizing the community’s engagement and the spiritual significance of the practices.

In his approach, Vollmann is conscious of the historical context and strives to avoid the exoticization often associated with Western portrayals of non-Western rituals. His work reflects a commitment to presenting the Djambi ritual with authenticity and respect, offering viewers an insightful glimpse into the cultural fabric of São Tomé and Príncipe.

What first drew your attention to Djambi, and what sparked the curiosity strong enough to follow through and document it—not just once, but multiple times?

I first heard about Djambi through a passing conversation—one of those moments where someone says something almost in code, assuming you already know what they mean. But I didn’t. The word lingered with me. As I began to understand that Djambi wasn’t just a ritual, but a deeply embodied response to loss, spirit, and collective healing, my curiosity turned into something more like responsibility.

As a photographer, I’m drawn to moments where presence overrides performance—where something real and ancient pulses through a community. Djambi had that energy. I didn’t go looking for it as a “subject.” I was called, in a way, by the people who live it and carry it. That’s why I returned. Each ceremony opened a new door, not just into the ritual itself, but into how grief, rhythm, and remembrance are interwoven. I kept coming back not out of repetition, but because each experience felt like a new layer being revealed.

You described a moment of hesitation, sitting in the car, sensing the intimacy and sacredness of the ceremony. What shifted in you emotionally or spiritually when the ceremony master called you in?

That moment was a quiet turning point. Sitting in the car, I was overwhelmed by the awareness that I was not just arriving at an event—I was stepping into a sacred space shaped by centuries of pain, resistance, healing, and devotion. I felt the weight of not belonging, of being an observer with a camera, and the responsibility that comes with that.

When the Master called me in, something shifted—not just in terms of access, but in trust. I understood that I was being invited, not just allowed. And that distinction matters. Emotionally, it grounded me. Spiritually, it humbled me. I knew from that point forward, my presence had to be shaped by listening first. The camera would come second.

Can you walk us through the very first Djambi you witnessed—how did it affect your understanding of grief, spirit, and community? Did anything surprise or challenge your previous ideas?

The first Djambi ceremony was overwhelming in the best sense. It was intense, physical, emotional—everything happened at once: rhythm, possession, grief, laughter, sweat, smoke. It wasn’t performative, and yet it was profoundly expressive. What struck me was how openly grief and healing lived side by side. There was no separation between the spiritual and the social, between the sacred and the sensory.

Coming from a Western context, where grief is often internalised, quiet, or medicalised, I was challenged—deeply—by the way pain was made visible and collective. That challenged my assumptions, but it also expanded my understanding of what community care can look like. The ceremony was not “violent” or “raw” in a destructive sense—it was honest. And in that honesty, it was deeply generous.

You left your camera in the car out of respect. How do you personally navigate the balance between documenting sacred traditions and honoring the privacy or vulnerability of those involved?

It’s a question I carry constantly—and not one I ever consider fully answered. For me, it starts with listening, with asking for consent in ways that go beyond a verbal “yes.” Just because something can be photographed doesn’t mean it should be. I try to feel when the camera is a bridge and when it’s a barrier.

Especially in post-colonial contexts, it’s crucial not to extract images but to build relationships. I don’t see myself as someone who “captures” something foreign—I see myself as a guest, and my photography as a record of presence, not ownership. That’s why I sometimes choose not to shoot at all. That absence can be more truthful than the most beautiful image.

In your third Djambi, you spent two days with Master Pajo and his team. What did that extended time allow you to understand or experience that a shorter visit might not have revealed?

Time is everything. Being there for two full days allowed me to witness the ceremony not just as an event, but as a rhythm that builds, contracts, and expands. I saw the fatigue, the preparation, the laughter during meals, the silences between the drums. These moments are invisible in shorter visits, but they’re where trust lives.

It also allowed me to understand that Djambi is not a spectacle—it’s a process. It moves through layers: the mass in the church, the slow buildup of the procession, the gathering of community, the descent into trance, the exhaustion afterward. In that time, I was no longer just photographing; I was participating through witnessing. That distinction changed everything.

You mention being ‘pushed’ into the crowd by a ceremony master. What role did physical movement and sound—like the drums and bass—play in how you perceived and captured the energy of the ritual?

The moment I was nudged into the crowd, it was like being absorbed into a living body. The drums weren’t background—they were heartbeat. Movement wasn’t choreography—it was necessity. I couldn’t stay still even if I tried.

Sound and movement in Djambi are transformative—they shape how space is felt, how time is experienced. As a photographer, it changed my approach. I couldn’t frame the ritual from the outside; I had to move with it, feel with it. The images from that moment are less “composed” and more inhabited—they carry the vibration of being inside something alive.

You write about being entrusted with this experience, that the ceremony was shown to you with ‘love and respect.’ How does that trust shape the way you share the images with the outside world?

That trust is everything. It’s a reminder that my role is not to explain or simplify, but to honor complexity. When someone entrusts you with access to their spiritual life, you hold that gift with care.

In sharing the images, I ask: Does this image reflect dignity? Does it amplify the voices and intentions of the people involved, or does it make them into symbols? I worked closely with the Master to contextualize the work. For me, showing the ceremony “with love and respect” means resisting the urge to over-translate or exoticize.

What do you hope viewers feel or reflect on when they see your photographs of Djambi—especially those who have no cultural reference point for what they’re witnessing?

I hope they feel unsettled—in a good way. I don’t want them to consume the images like cultural souvenirs. I want them to slow down, to feel the tension between beauty and unfamiliarity. Maybe even question what they expect sacredness to look like.

At the same time, I hope they sense the love, the care, the intention behind the ritual. I hope they feel that Djambi isn’t a “performance” for others—it’s a practice of grief, survival and healing. If my photographs can open a door to that recognition without flattening it into explanation, then I’ve done my part I hope.