This interview has been transcribed to preserve the speaker’s core message.

Can you tell us about your beginnings in photography and how you landed your first photography job with the New York City Summer Work Program in 1975?

I was fascinated with being able to draw and um, sketch and I thought I’d probably want to branch off into painting, either watercolor or oils. And I realized very quickly that I could not draw.

I was awful. I had friends of mine that could just look at something and sketch it to perspective. And I knew I was not born with that skill. And I had no idea if I could ever learn to do that. And so, I was, uh, my father had been messing around with photography and he He had left a camera after he and my, and, and, uh, he and Ma split up.

He left a camera around and I got fascinated with a light gadget. So this was a new gadget. So I, uh, had no idea the thing wasn’t working, but I put film in it. And I’d walk around and I’d take pictures with it. Anyway, I finally got a real camera that worked. And, uh, I saw things in my, the way I saw something.

And the way it looked, I was fascinated how light made things look. And so, I would snap a picture of it, and someone had a darkroom, and I went, you know, we shared the darkroom, and I learned how to process film. And after a while, among all of our friends, every time I took a picture of something, it came out, just like I saw it in my mind.

I didn’t know that this was An amazing thing to be able to do. I didn’t know that people work years to do this and couldn’t do it. But I could just do it. And when I realized that, uh, I was scared because I was afraid this, this gift that I’d been given would leave me. And so I started finding ways to learn how to be consistent.

I started reading books. I started looking at other photographers, uh, the old masters and, uh. I quickly also learned that, you know, you better be good at, uh, learn to learn to process film and how not to cut corners, doing that, uh, maintain your temperatures. I was got very good at processing film. And, um, I knew by the time I was 17 years old, this is what I want to do the rest of my life.

Um, so we’ll speed up a little bit here. Uh, I went to college. The college I went to did not offer, they weren’t a college where you could go get a degree in the arts. You know, like, uh, painting, drawing, photography, things like that. And they tried to steer me away from wanting to pursue a career as a photographer.

So I only went there for one year. And they were in Oakwood College in Huntsville, Alabama. I then, uh, left there my first year, and I ended up going to New York and staying at my uncle’s house. And when there we did in Queens, he said, Hey, uh, uh, the city, he worked for, he was a chemist and he worked for the city.

He said, they’re looking for a photographer. And so you should, you know, he says, I’ll give you the name of the person. So he gave me the name and I took some of my, my work and they hired me. I was in heaven. And, uh, I think I worked there for them for almost nine months. And I had, you know, I shot all the things going on in New York during the summer and afterwards for their newspaper.

And, uh, you know, I was riding subways, uh, it was the height of the disco era. So, it was amazing that, uh, you know, all that music, all the energy of the city, um, You know, summers in New York are, wow, spring and summers in New York are wonderful. I haven’t had, I’ve never had a bad time in the city. Anyway, that job ran out and, um, I ended up, uh, moving to L.

A. because my father was living here and I needed a place to stay. And it just goes on from there.

What is it like capturing vibrant events of the disco era? Music festivals, block parties, during your time with New York City’s Summer Work Program?

man, it was magic. Uh, you know, they would, uh, sponsor parties in Harlem and in Spanish Harlem and, uh, and in, uh, uh, Hell’s Kitchen. And the party I remember was, uh, going to shoot, uh, a Borinquen party, block party, in, uh, Spanish Harlem.

And, uh, You know, the music, man, the drums, the dancing, uh, the party start like at 12 noon and they go on until the next day. Um, and I remember everybody was screaming for rum and Coca, and I didn’t know what that was. I just wanted to drink a Coca Cola. Someone who had me a glass, what I thought was Coca Cola.

And it was, uh, two thirds, uh, Bacardi one, five, one, you know, 151 proof rum and Coke. with a cube of ice in it. And, uh, I drank one of those and, uh, I quickly recovered, you know, and the rest of the time I made sure I got Coca Cola, but it was, it was amazing. I got some great shots. Uh, you know, the, the music and everything else.

Yeah. Um,

I came to LA and worked part time at Sears. Uh, IBM, I was told that IBM was starting to hire. They hadn’t hired in a while. And I got an interview. And I, I, uh, did very well on the interview. And they said to me as I was leaving that they were going to call me. I did not believe them. And seven months later they called me.

And I went through six months of intense training on their, their typewriters. The typewriter with the ball and the regular typewriters and their dictation equipment. And And, uh, this was the first real money ever made in my life. So I was able to buy any camera I wanted, you know, and I, uh, I actually slowed down in photography when I was working for IBM for three years.

I didn’t take very many pictures at all, but I did buy, um, a very good enlarger and kept on processing film. Uh, at that point, my, my only camera was a Leica M5 with a 90 millimeter, uh, lens. So I had to learn to focus that camera with a 90 millimeter telephoto. So that’s, uh, that’s like, um, you’re, you’re handicapping yourself when you’re target shooting to where you cover both your eyes almost with a tiny little slit and you have to see your target and hit it through that little tiny slit in the window.

But it taught me how to focus a range finder.

So, I was there with IBM and after, um, almost four years I realized that I was not going to, I was not going to, um, become, uh, a corporate guy. I, I, I like working in the field. I like being outside with fresh air. And, um, to get a promotion you get promoted into an office. And all of the people I saw in the office, they didn’t look happy.

And I went to lunch with one of the guys that had been there for 10 years. And, um, I said, how long have you been here? And he got this look on his face. And I, right there, I decided I don’t want to ever have a look on my face like that again. I don’t want to have a look on my face. And I went in a week later and I told him I gave my, uh, my separation notice.

I told my boss I was going to quit. He couldn’t believe it. But I said, I’m not happy here. And I said, it’s a great company and everything, but I’m not happy here. I want to go back to being a photographer. And, um, because of that, um, I freelanced for a little while in photography and made decent money. And I decided I wanted a full time job.

So I took a job at Transamerica Occidental Life as a, uh, they were, they needed someone that knew how to fix IBM typewriters. And I figured I could do this. I could do that job in my sleep because I was trained so well to work at IB at, uh, IBM. And so I started saving money and I signed a lease on a loft space.

And I figured once I got my loft space I’d get my business going and I’d quit working at Transamerica and freelance photography. But, uh, the, uh, God had a different plan for me. One of the guys that was working with me in the repair shop at Transamerica convinced me to enter an employee art contest. And, um, I won first place.

And next thing, you know, besides me working for them full time in the daytime, uh, as a repairman and IBM equipment, they would separately hire me to shoot some of their events and their, their, uh, product photography. Cause I learned how to do that. And pretty soon I met one of the top executives and they surprised me and offered me a full time job as their corporate photographer.

That’s how it started me and my first real professional work. And, um, they insured the 84 Olympics. So I had to shoot that kind of thing. I could do that. Um, they flew me out of the country for, to cover their top meetings because I was shooting their annual reports. I was doing their corporate portraits.

I was doing their community affairs things. I was shooting all these different jobs, you know. Um, and it gave me, you know, uh, Around about around about training to where I was comfortable shooting all kinds of photography, but don’t get, don’t get it. Don’t, don’t get, let me, let me, let me, um, clarify something.

I’ve always been fine art first. So what I learned when you’re dealing with people who aren’t in living in the art world is if you’re a photographer and you’re working for someone, You’re basically problem solving their visual needs. So, you gotta be careful how artsy you wanna be unless it can work for them.

And you need someone that understands that. Uh, you know.

Your fascination with light is evident in your work. Can you share why light is so important in your photography and how you utilize it to enhance your images?

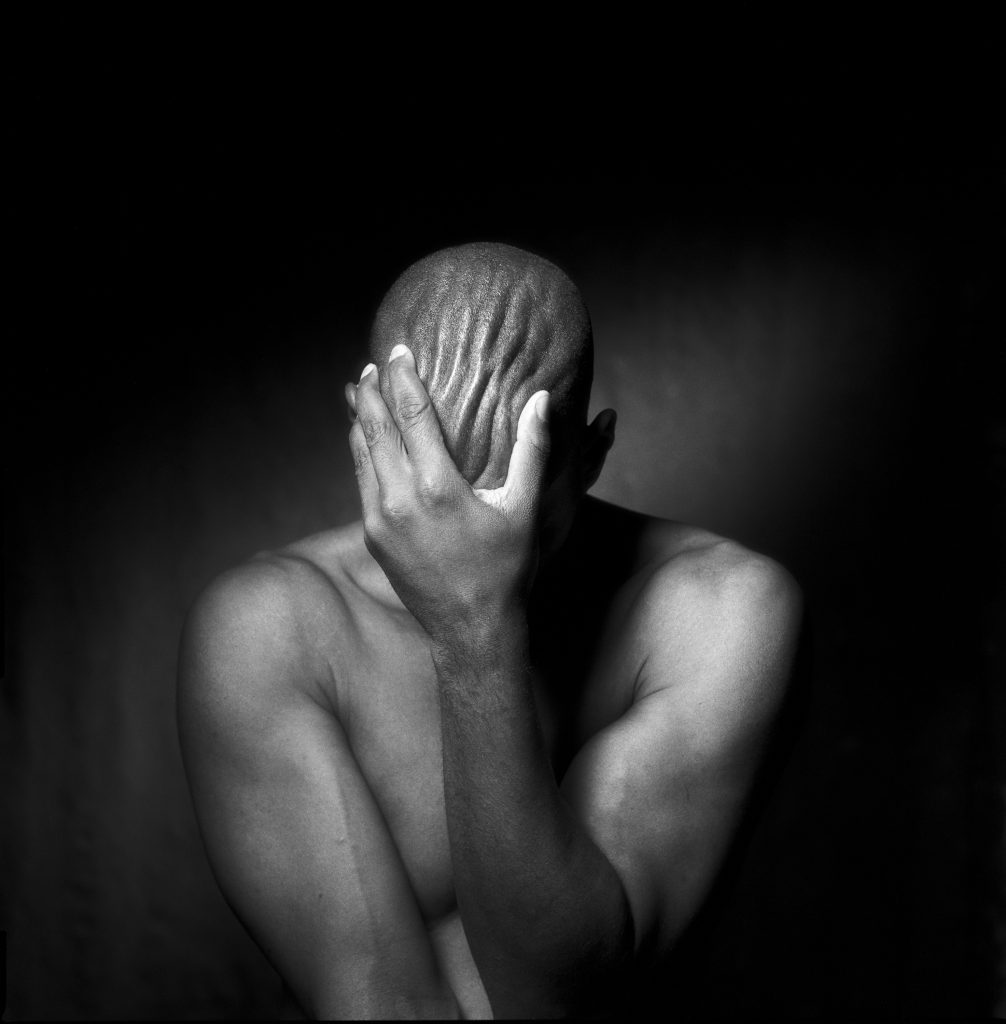

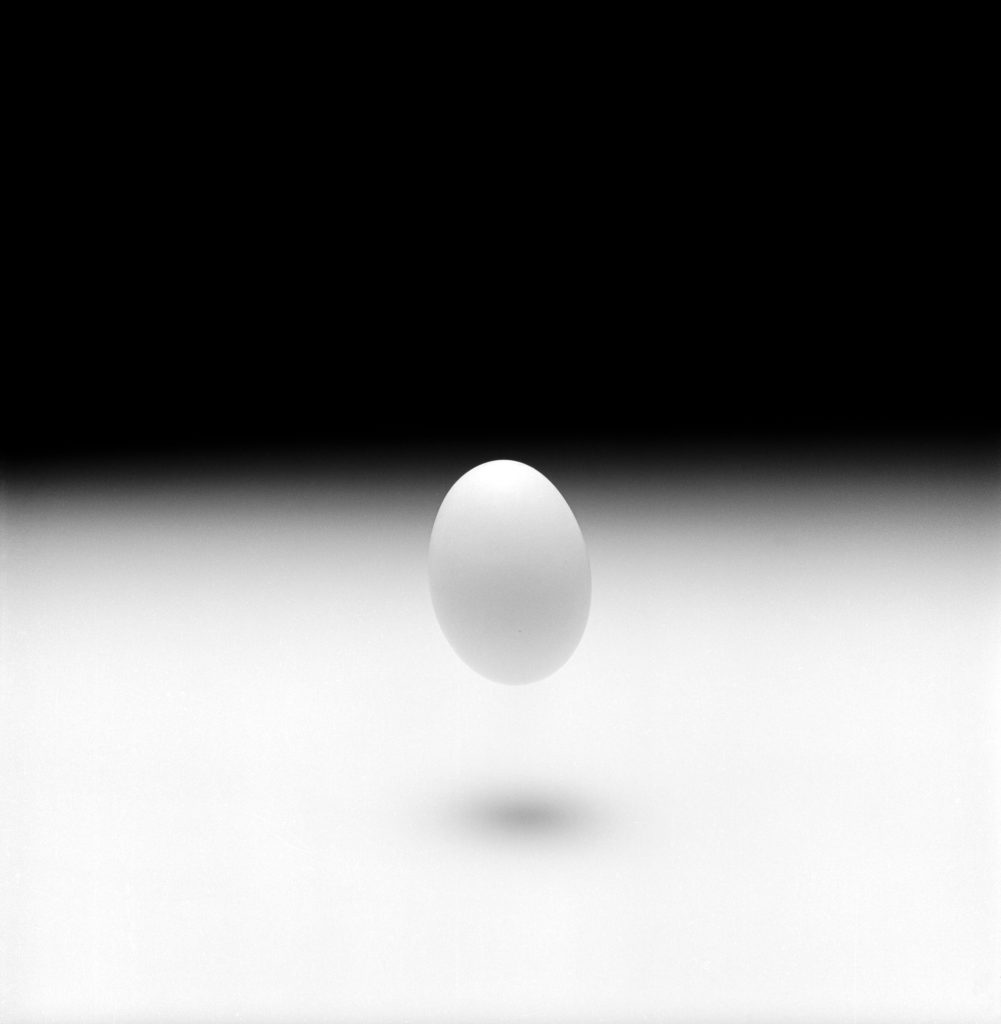

I’ve always been fascinated with light. And the thing that drives me and the gift I was given was I realized I was very good at seeing light and how to use it, uh, how I can use light to add depth and drama and feeling to a picture because it’s not what the, what you’re shooting.

It’s how the light makes you, how light makes it look. And that’s how it makes you feel. That’s the power of art, how it makes you feel because art speaks to everyone separately. You know, it’s something that, uh, you’re attracted to will reach out and, and, um, grab your soul, you know, it holds you, you know,

You choose to shoot primarily in black and white. What draws you to this style, and how does it influence the emotion and storytelling in your photographs?

so I learned, uh, to shoot in color while I’m equally comfortable with shooting in color or in black and white, but I really shoot most of my fire and art things in black and white.

Because without the colors, you’re able to see the light differences and feel the work. It gives you the power, the power of the work. Um, the emotion. And, you know, each picture that you see that attracts you, there’s a story, photographer has a story, but sometimes it can give you a story of your own, you know.

And, uh, you know, try that. Try to look at a picture. And what does it make you think about? Was it bringing back something that, uh, maybe an experience you had? And then maybe you can meet the photographer that took it and ask them something about, you know, ask them their thoughts on the picture. See what they have to say.

Your approach to gear has evolved over the years, from owning multiple film cameras to now primarily using one camera and lens. What influenced this shift, and how has it impacted your work?

Um, I’ve owned, I used to dream about owning certain cameras like a Hasselblad or a Leica or that Nikon. And I got to a point where I became the guy that could do that. And you know, what I’ve learned about cameras is, uh, cameras are just tools. Um, I’ve got my favorites, uh, my favorite film camera, and it always will be, uh, first and foremost was my Leica.

Uh, I got rid of them five years ago. I still kept, I bought an M6. I still have it. It’s a custom is only one of these. I had some custom work done to it. So it’s more like what they call an M6J. It’s a, it’s an M6 Leica with a green leather and it’s got my logo on it. Uh, no leather. And it has M3 levers. All the levers, the film wind and everything else is, uh, from an M3.

So I really like this camera. It’s baby goes out with me every day. Um, along with my digital kit, my digital kit is Sony. I like their cameras. They work very well. They’re all the focusing is pristine. And I’m able to make my black and white digital, uh, images out of this Sony look just like they’re black and white.

So I like the fact of being able to do that. Um, um, I kept my, uh, my Hasselblad kit. I love that camera, a film Hasselblad. Um, I’ll always keep that camera. I still use it. And, uh, I used to shoot eight by 10. I got rid of that. And I kept a four by five camera. Um, you know, being able to move between these sizes and formats has helped, helped me to know how to adjust my digital files.

So they look more like film.

You have an upcoming exhibition at the Icon Los Angeles. Can you tell us what to expect from this show and what themes or subjects you are most excited to present?

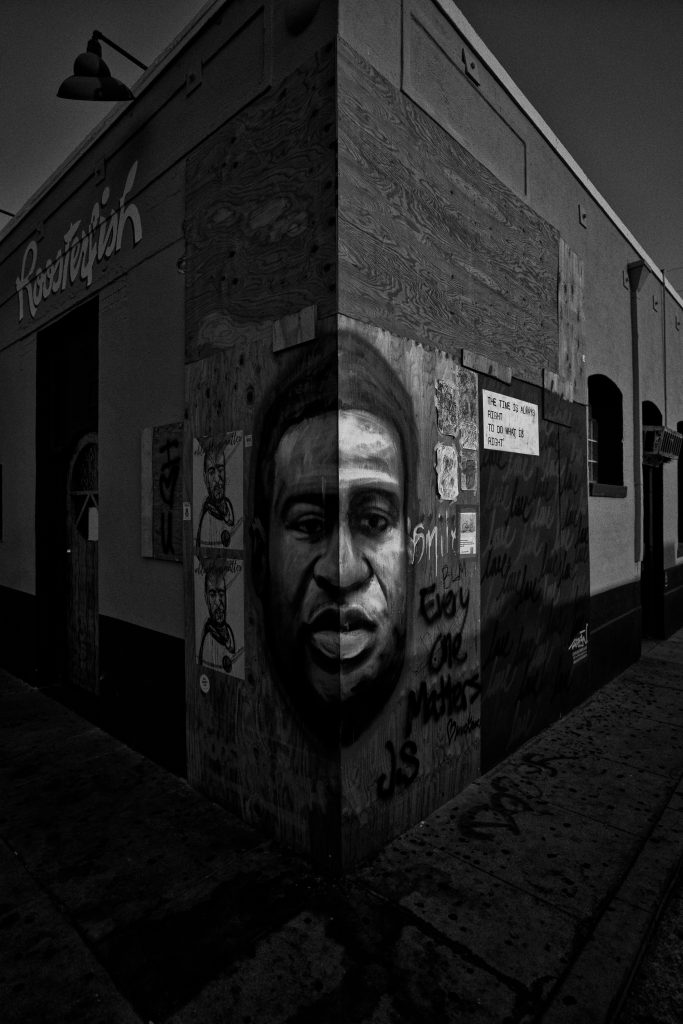

Um, I have an upcoming exhibition at, uh, The Icon Lab Gallery in Los Angeles. And, um, I call the show At Sea Level. You know, and At Sea Level is about what I’m about, which is ubiquity. Ubiquity is ubiquitous. The ability to be present in a space, but in all spaces equally, but you’re aware and present and you’re able to do everything very well.

You’re not half doing this and overdoing that. Um, the Latin word for ubiquity is ubiquitous. Um, at sea level. Is my place of vision. When I go to that spot, I’m seeing and not thinking I’m seeing, not thinking. And when I go there, if I see something that makes me want to take a picture, because the light, the light makes me stop how the light is on something.

And I won’t think about, I’ll shoot it. And I’ll worry about whether I like it that much later. And I never threw away any film shots and I don’t throw away any of my digital files. And I also don’t. Just snap pictures just to snap them. I’ll snap one or two and then I move on. And I wait till I get to When I’m out shooting I very rarely review them on the back of the camera Because you’re missing life going on and all the moments around you Uh, what I do is I get back to the computer.

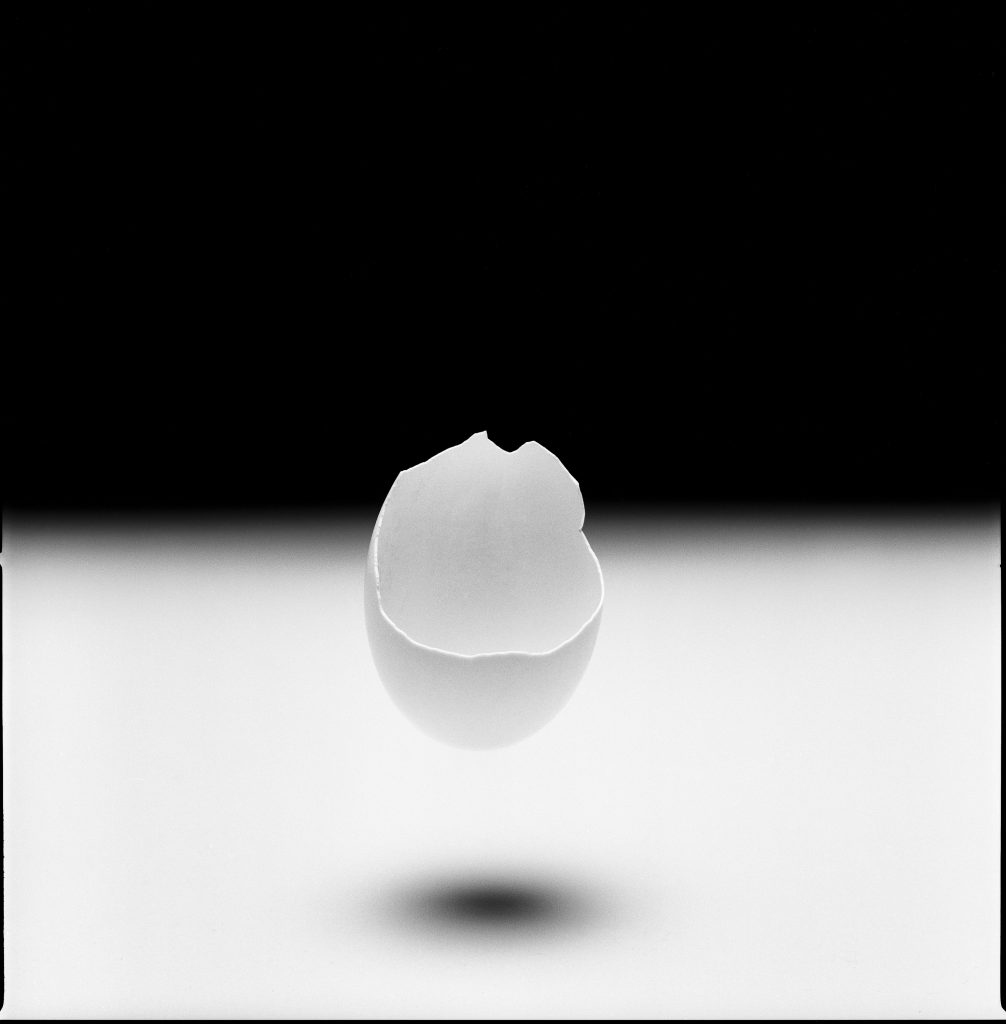

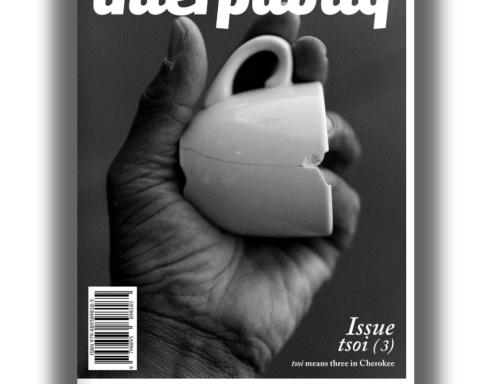

I can really look at them So I can see all the details Um, but this show is about that it’s called that’s at sea level people Places, things, and uh, I love coffee. So I have a project where I’ve been shooting, uh, the coffee cups people leave on tables, and I would wait for, I’d watch someone at one of the coffee houses, and, uh, and I would shoot what they left.

It was sort of like a, humans were here, someone was here, and this is their signature. And, uh, that was in 89, and, and, uh, I was traveling in, in Holland, and And I realized that that’s just one side of it. I needed to, uh, the cups, I just shoot them. I wouldn’t touch anything. I needed something controlled. So I was having a coffee with this wonderful cup and saucer and my friend worked at the coffee house.

And I said, I like this cup and sauce. He said, put it in your pocket. That was 2000. So from 2000 even till now, I still shoot cups as I find them, but I also posed this cup from different times. And I’ve been able to get the cup in the hands of some famous people to take a picture and hold on the cup. Um, in 2015, I managed to break it in three pieces and, um, I like it even more now because I decided to glue it back together again.

And it looks like me. It’s got some cracks and scars on it. So, you know, some wear and tear, like a nice brass camera that you use a lot. But, um, You know, I’m constantly evolving, and constantly looking for more moments to capture. You know, the, uh, the, uh, active purpose of documenting life is, life is broken down in moments.

And when you start capturing moments with a camera, you know, that is what Photography is, and the end, the last part of that is you have to make prints. You have to print. If you’re not printing, why are you taking pictures? Why are you spending thousands of dollars on camera equipment or 2, 000 on a phone?

And you take these beautiful pictures and you’re not printing them. Makes no sense. You have to print. So I’m actively Finding this and that moment and moments, and I’m simply happy to become the sum of my moments.